Thomas Reiner

A transcript of a speech delivered by Thomas Reiner at B’nai Jeshurun on Yom Kippur 2006.

By putting aside these minutes, Rabbi Roly, Marcelo and Felicia have made sure that the events of this past century remain in our memory. I would like to note Myriam Abramowicz’s part in making sure that each year’s Yom Kippur gives fitting acknowledgement to this. I want to deeply thank my wife, Susan Lieberman Landau, for encouraging me and pushing me towards the difficult, even painful decision to be here before you.

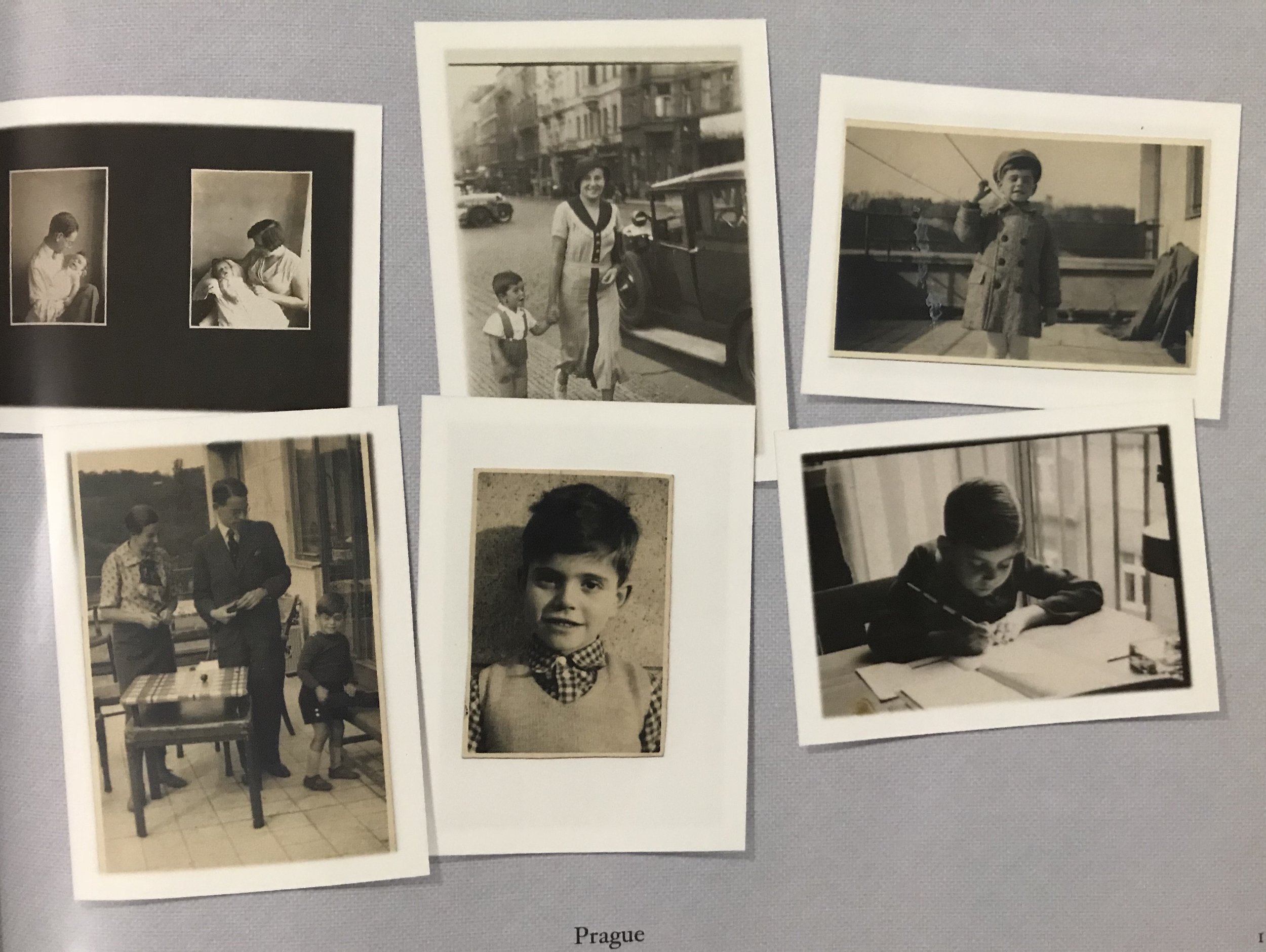

Let me share some images I have from the ‘30s and the war years and then add some reflections on living through the decade which partly and distinctly define us as Jews. I will end with some reflections on the different kinds of survival.

“I sensed tension as I showed my father the German batch, with Hitler’s portrait on each stamp”

It is 1936; I am 5 years old. We live in Prague. I have just started collecting stamps and get great pleasure in knowing how to place the ones I get into separate country piles. I recall even now that I sensed tension as I showed my father the German batch, with Hitler’s portrait on each stamp. The moustache with something laughable but there was also something fearsome about it. I test the waters as any child that age might: I point to the stamps and with knowledge, perhaps picked up in kindergarten, give a “Heil Hitler,” followed by a sharp rebuke from my father.

Fast-forward two years. A strange, out of synch, long fall week in the country, at the village home of my cousin’s nanny. I hear the word “Munich,” talk about invasion, reference to bombing—as in the newsreels I have seen from Spain? All this somehow tied to the rasping voice I’ve heard on the German radio station; to the flight my father took on business to far-off London; to the imminent departure for America of my aunt and uncle and cousin. Those months during 1938 also bring new visitors to our home: refugees from Germany. I formed a friendship with a boy from Berlin. My mother was their family social worker.

I know that for some years my parents had sought that elusive visa which wouldhave allowed us entry into the U.S. By 1937, they struggled to get out from what they correctly assessed as an imminent maelstrom, though for sure the image of the future could not have pictured the catastrophic nature of the Shoah. There must have been some ambivalence to their efforts, as there was with most of their peers at the time. They were very successful in Prague. Later, they labeled themselves and their friends as “Czuppies” (a play on yuppies). They led a good life and were comfortably integrated in the Czech world. Nevertheless, they felt vulnerable, something which was transmitted to me even in early childhood.

I have at times jokingly referred to my parents as orthodox— orthodox atheists. They were secular lefties, my father the first generation in his family with a university education, immersed in the cultural, aesthetic, political, societal blossoming of interwar central Europe.

And they were well off beyond the dreams and understanding of those in the previous generation: By the time they were 30, they left behind in one brief decade poverty and even hunger. They were scornful of what they felt was the limited, old Jewish world of their parents. Perhaps hard to understand, they nevertheless still saw themselves as Jews, perhaps in the forefront of Jewishness. Their social group was virtually all Jewish, and though almost all avenues for participation and advancement were open to them, they were in tune with events abroad (and with the history of the now-fragmented Austro-Hungarian Empire). As such, they realized that they were at risk, at risk as Jews individually and as a group.

I now see they made sure that I, even at that early age, had survival skills. My parents took on a German émigré, named Dr. Katzenellenbogen, to teach me English. At his house, I learned from a book incongruously titled Laugh and Learn with gems such as: “I put my left arm on my right shoulder.” I played with his son. (After the war, we found Katzenellenboigen Sr. was SS, a plant in Prague to infiltrate the Jewish community—later he served as adjutant to Buchenwald’s Ilse Koch and in 1946 was convicted of war crimes.)

“The teacher calls my parents that evening, essentially urging them to teach me to shut up”

Our move from an elegant Bauhaus apartment to a seedy neighborhood was explained as the need to be less conspicuous. In the spring of 1939, my teacher asked who will be in the class in the fall so that the right number of midmorning snacks can be ordered. I brightly volunteered: “I won’t need any; we probably will be leaving” (hadn’t I heard such at home?). The teacher calls my parents that evening, essentially urging them to teach me to shut up, and so they did.

March 15, 1939. Prague capitulates to Germany, Hitler, the Nazis, Gestapo, SS—at 8 I had a sense of the overlap. Earlier in the dead of night my parents carried incriminating books and papers to dump them into the river, the Vltava or Moldau. Here is my own overriding image of that day: There was an insistence on normalcy, so we children go to school. As we are let out, I walk home, only to find I cannot cross our street: A phalanx of German tanks blocks my way to our building. For two or three hours, through the narrow space between the armor, I see my mother on the other sidewalk together with other anxious parents. I am fearful. Eventually we children are allowed to pass between; I reach my mother.

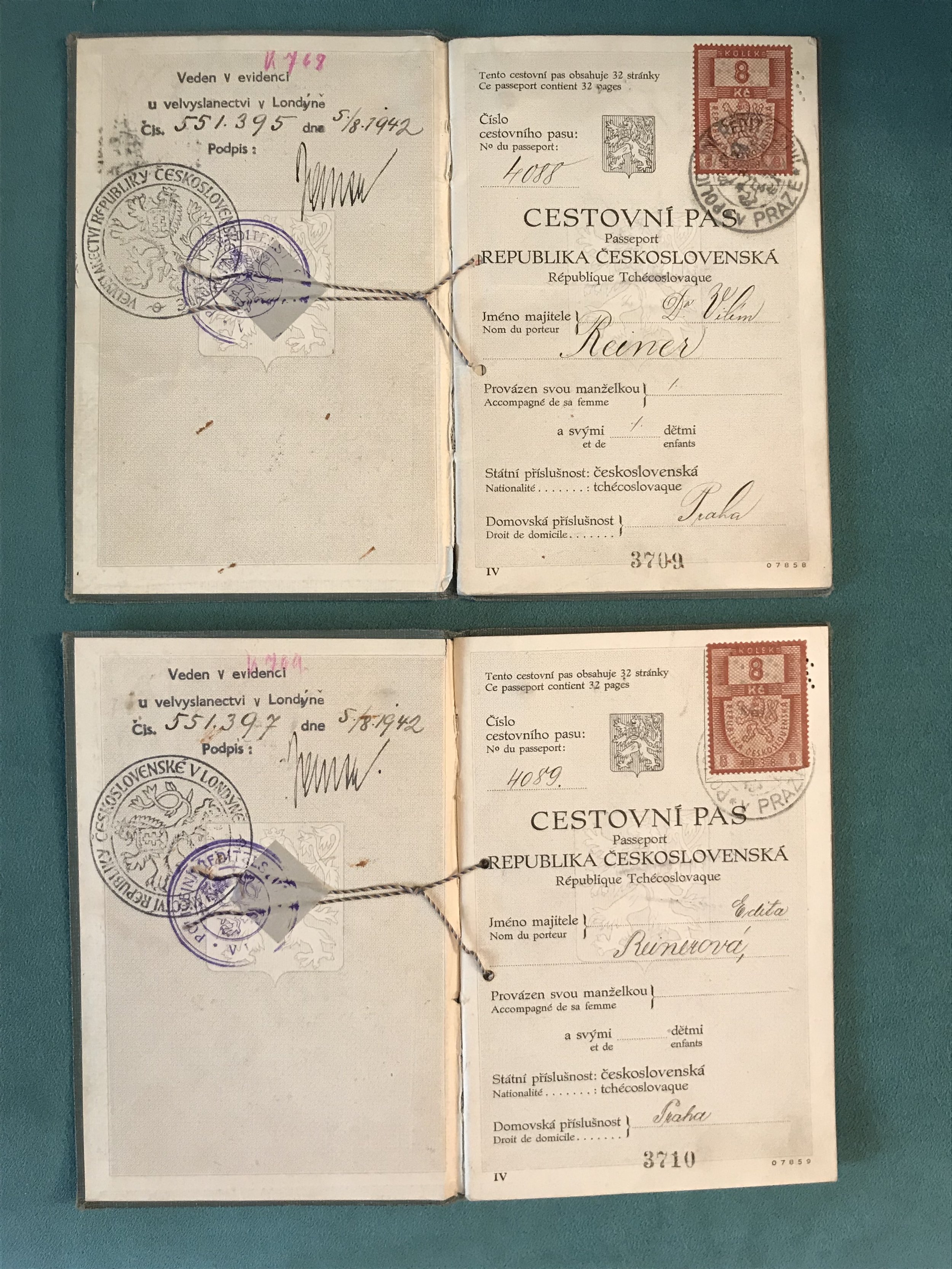

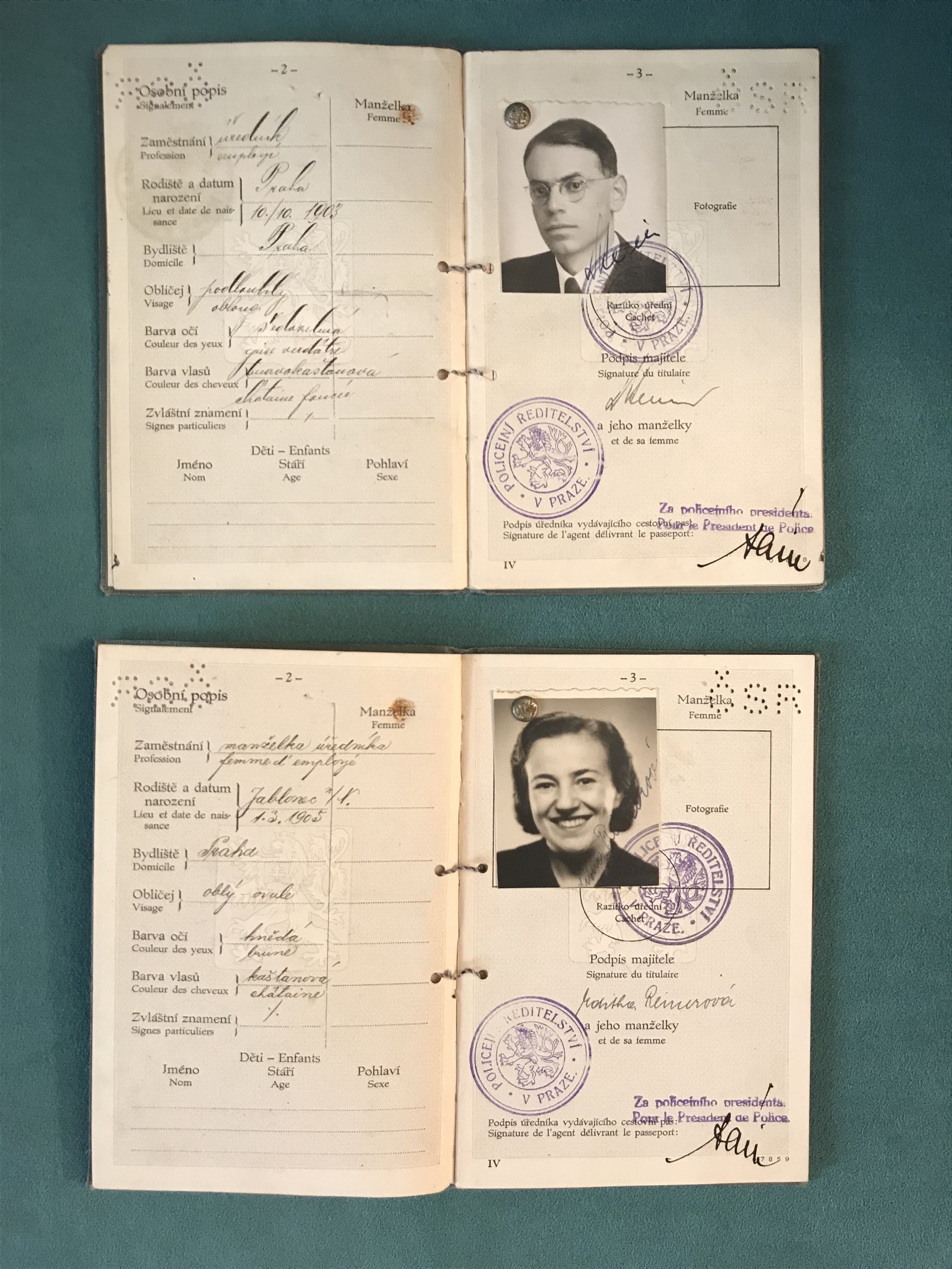

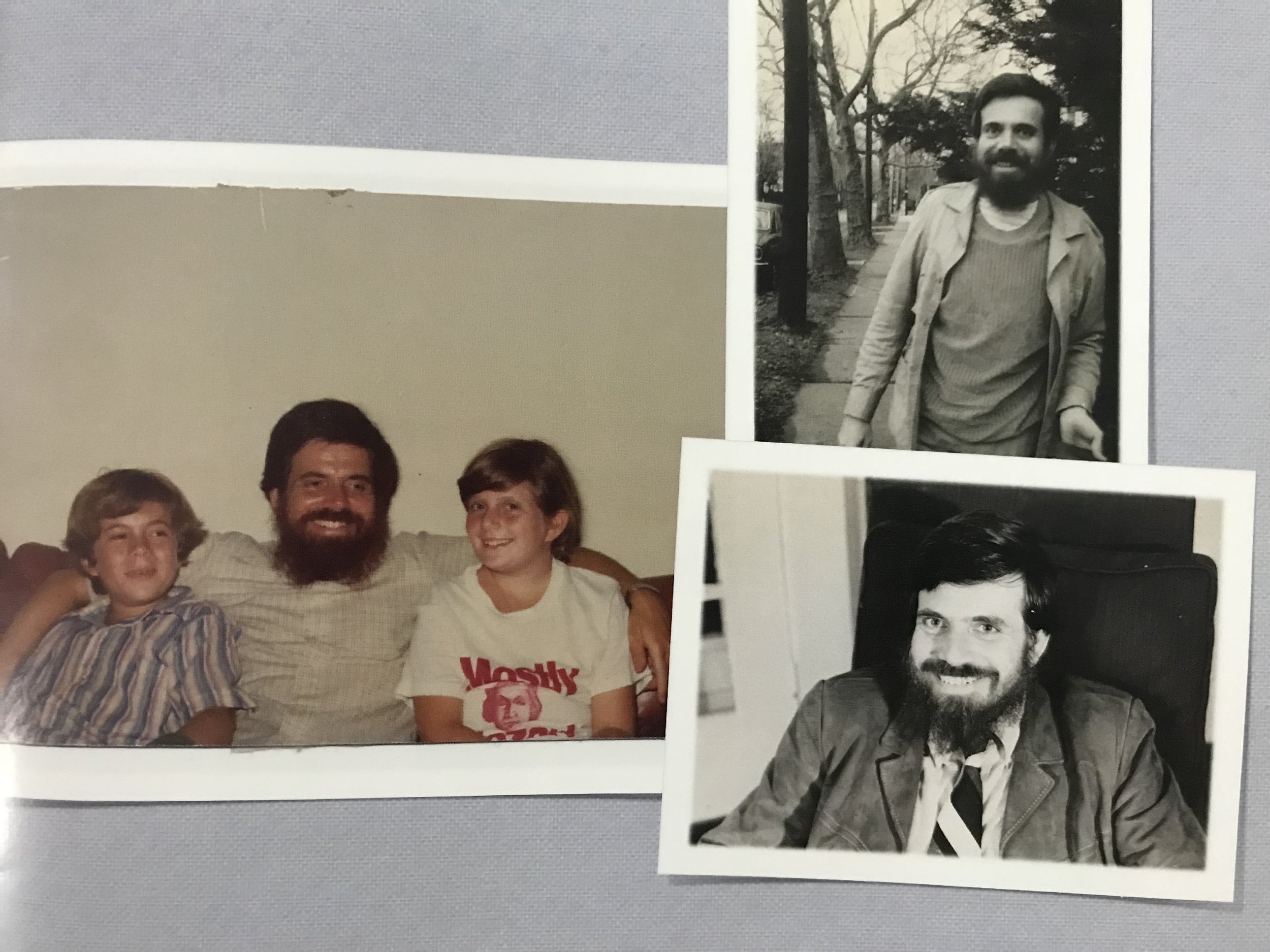

Tom Reiner’s parents, Vilém and Edita.

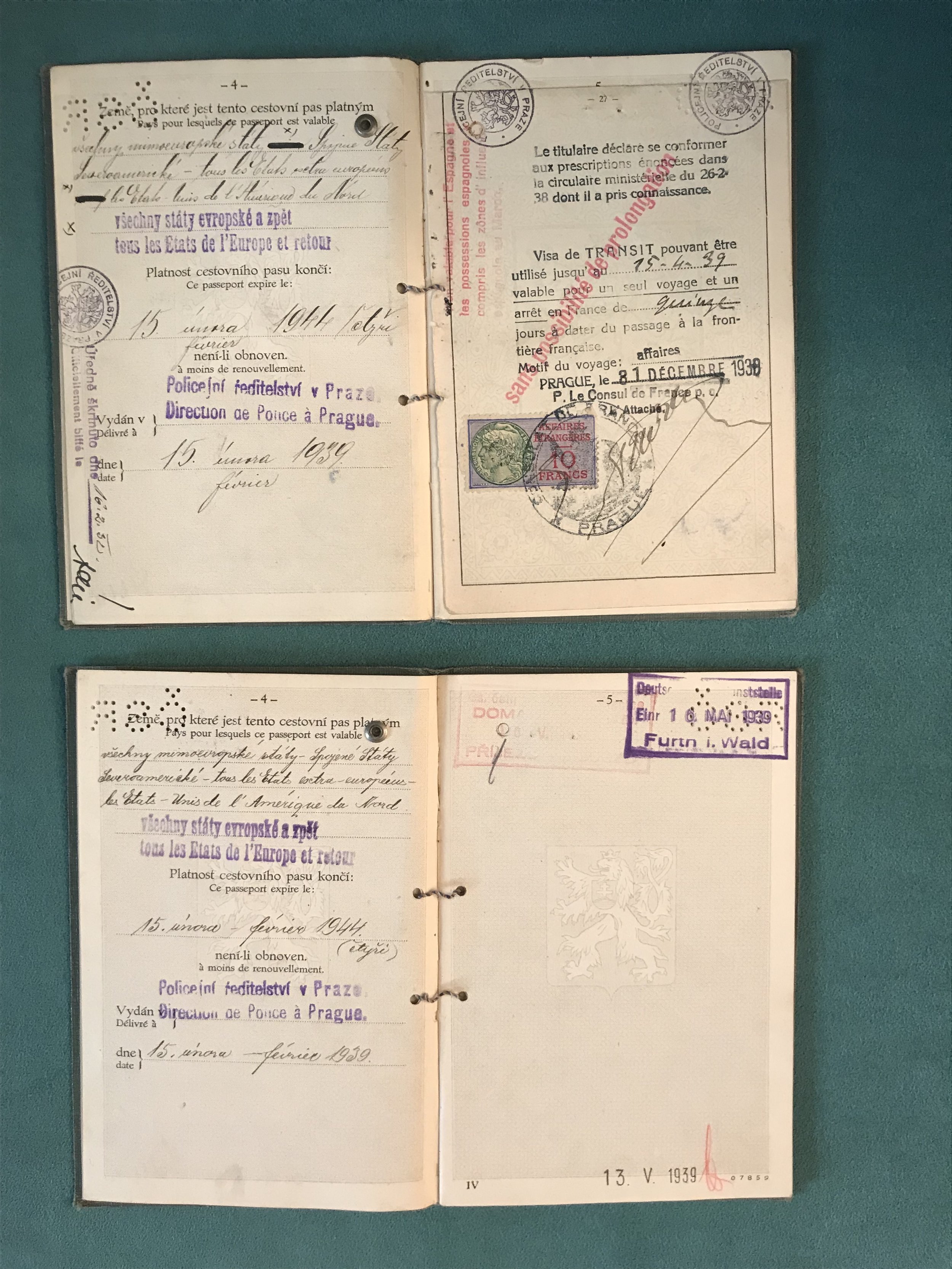

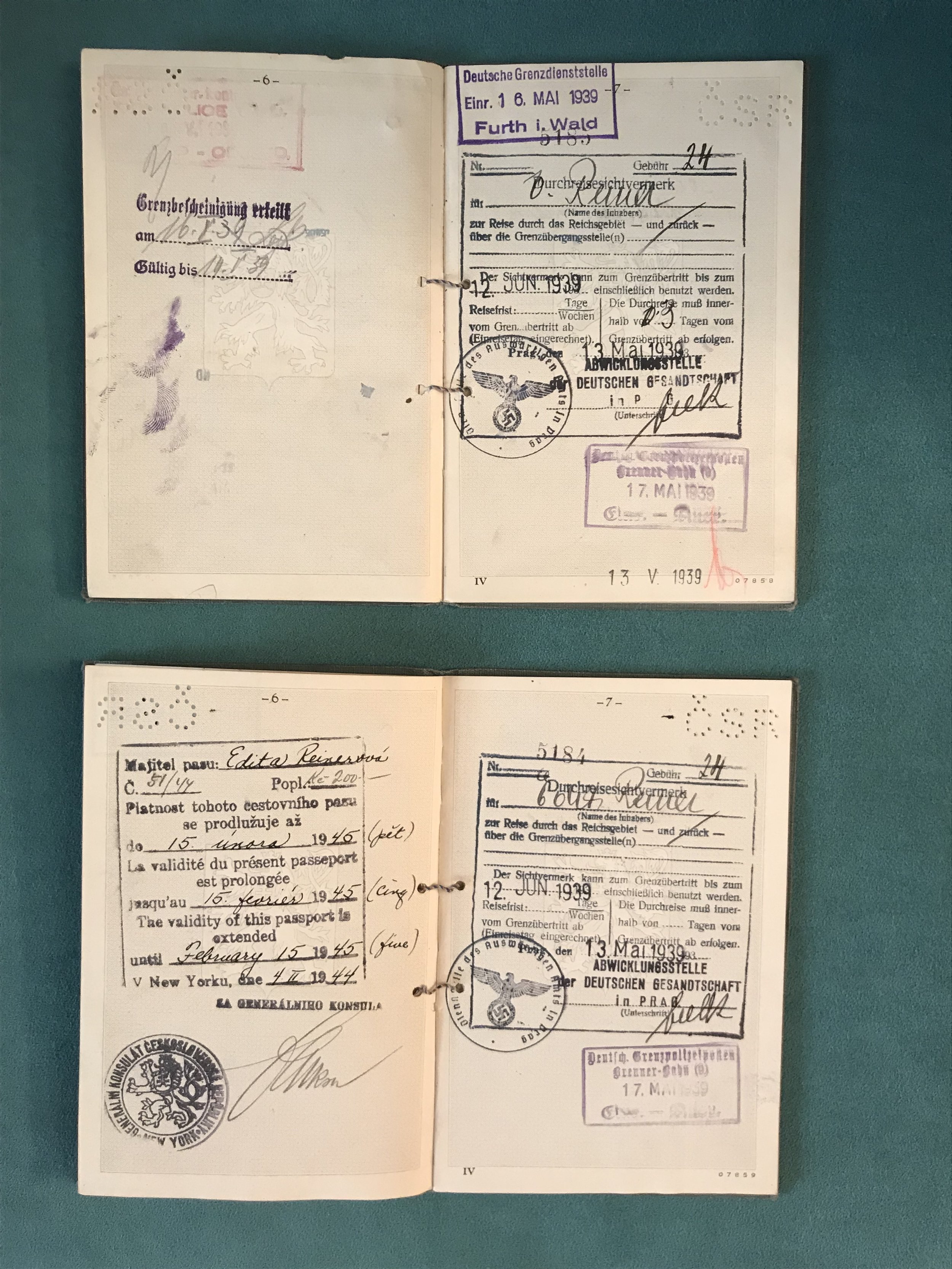

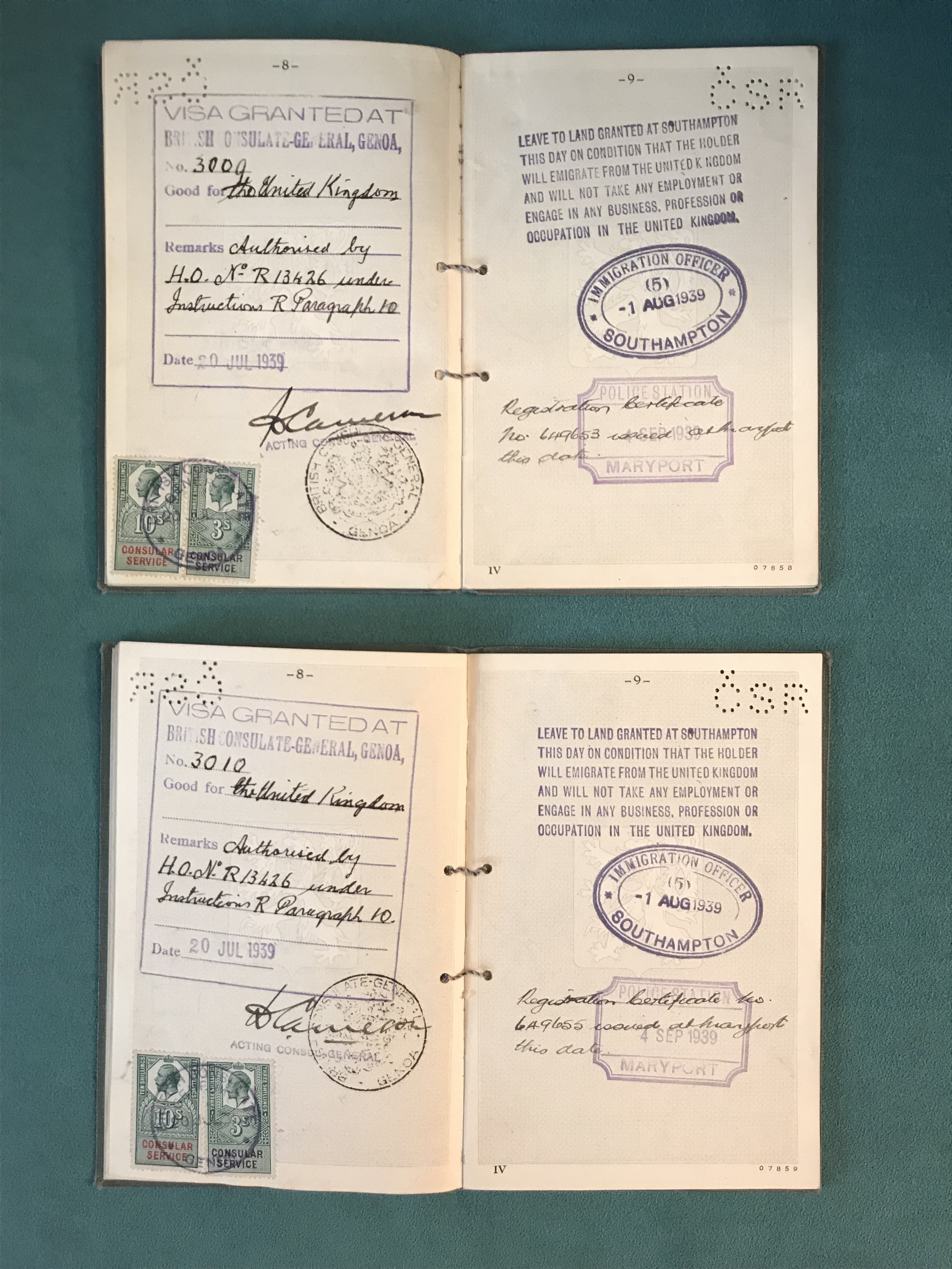

Exit—or better said, flight—became of greater urgency now, though reports from the first months of occupation suggest a quiet if fearful time. My name was put on a Kindertransport list for Holland. Fortunately I did not get to go. My parents without success sought entry anywhere in Western Europe; the only countries open to refugees were the Dominican Republic, China, and Italy—none attractive choices to them. My mother left our passports with a “fixer.” When she returned, the building super told her that the Gestapo had seized him and ransacked the apartment. She casually asked, as his “cousin,” for pass keys and let herself into his living room. She found the passports in the back of a desk drawer and took them home.

As on most days, she also stood on line in the Gestapo office to secure what now were necessary exit permits. May 15 the Gestapo officer in charge called down the queue for a translator. Silence: Who (though everyone would be fluent in German as well as Czech) would collaborate, but also in a way expose oneself? My mother sensed an opening: she volunteered.

End of the day. The officer slams shut the register and laughs: “That’s the end of this nonsense, no more permits.” My mother stands up, and says “Look, I have spent hours translating for others and for you. Give me three permits now; that’s the least you can do in turn.” As she told it, he was startled by her chutzpa, saying, “You’ve got nerve,” and stamped her three passports with permits.

“We tried to pass as a German family summering away from Prague.”

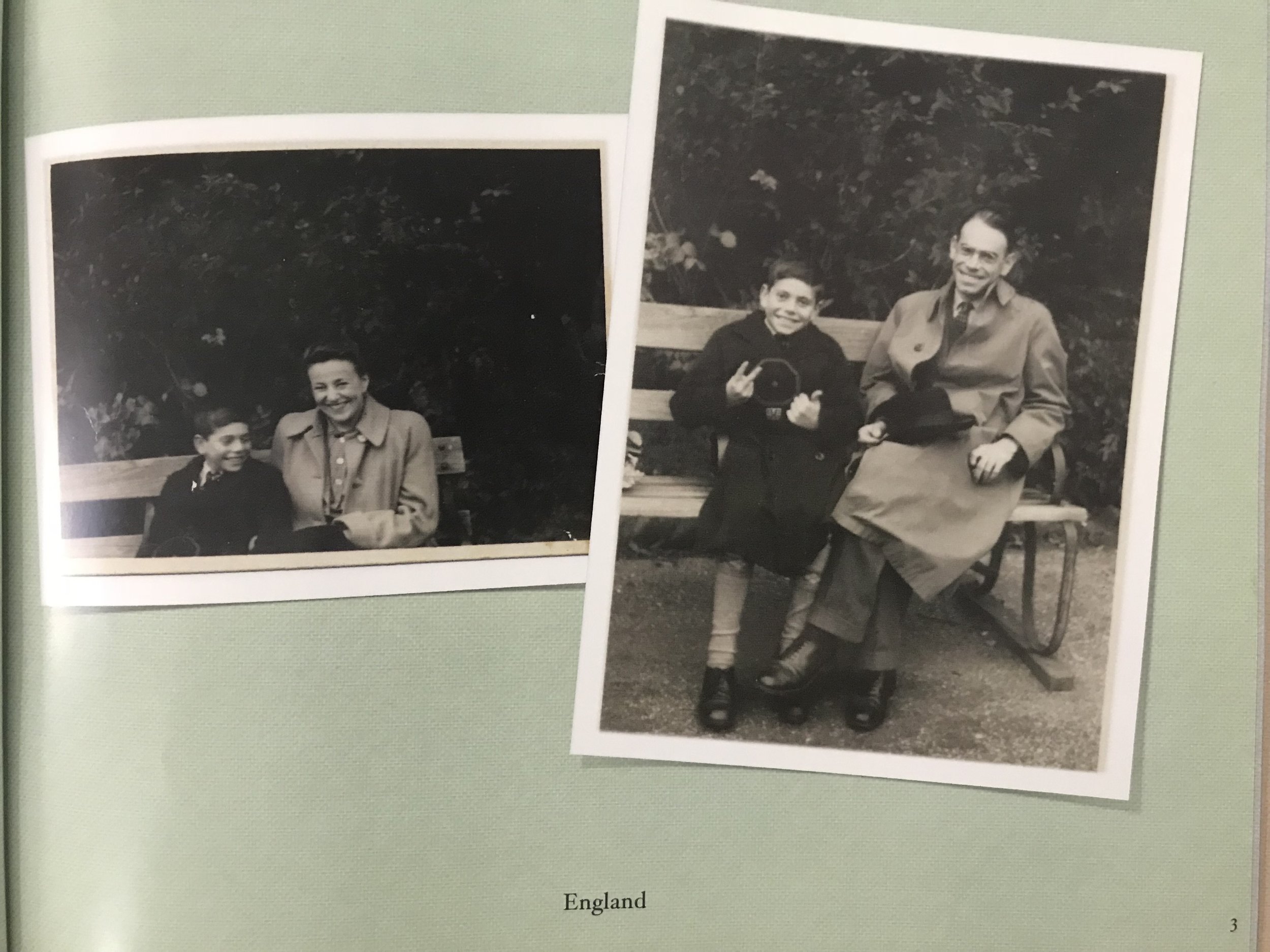

Two hours later we left, four suitcases in hand, for a new life en route to Italy, familiar from vacation days (and now at least a tolerable alternative). Changing trains at midnight in Munich, I remember I was told not to open my mouth. The summer of 1939: something of a holiday for me, on the Italian Riviera. We tried to pass as a German family summering away from Prague. Fascism seems not have touched us as we lived in surroundings known from earlier years. Short-term tourist visas were finally granted for passage to England. This stretched to more than three wartime years there, first as an evacuee with a Quaker family —pacifists, to my youthful chagrin—while my parents continued to seek in London that elusive American visa. Then back with my family in a small British town ravaged more by the Depression than by the War. A hundred Jewish refugees were gently absorbed in Maryport.

Still, memories of that time include demolition of our home one night by bombs (amazingly no injuries), and my elementary school a few blocks away was leveled too. But the war for me remained largely the BBC news, heralded by Big Ben, at nine each evening—and step by step more evident rationing. There also were idyllic bike trips through the nearby Lake District. My parents found work: my father, an attorney, incongruously as a traveling umbrella salesman in Scotland, and my mother as a bookkeeper in a clothing factory.

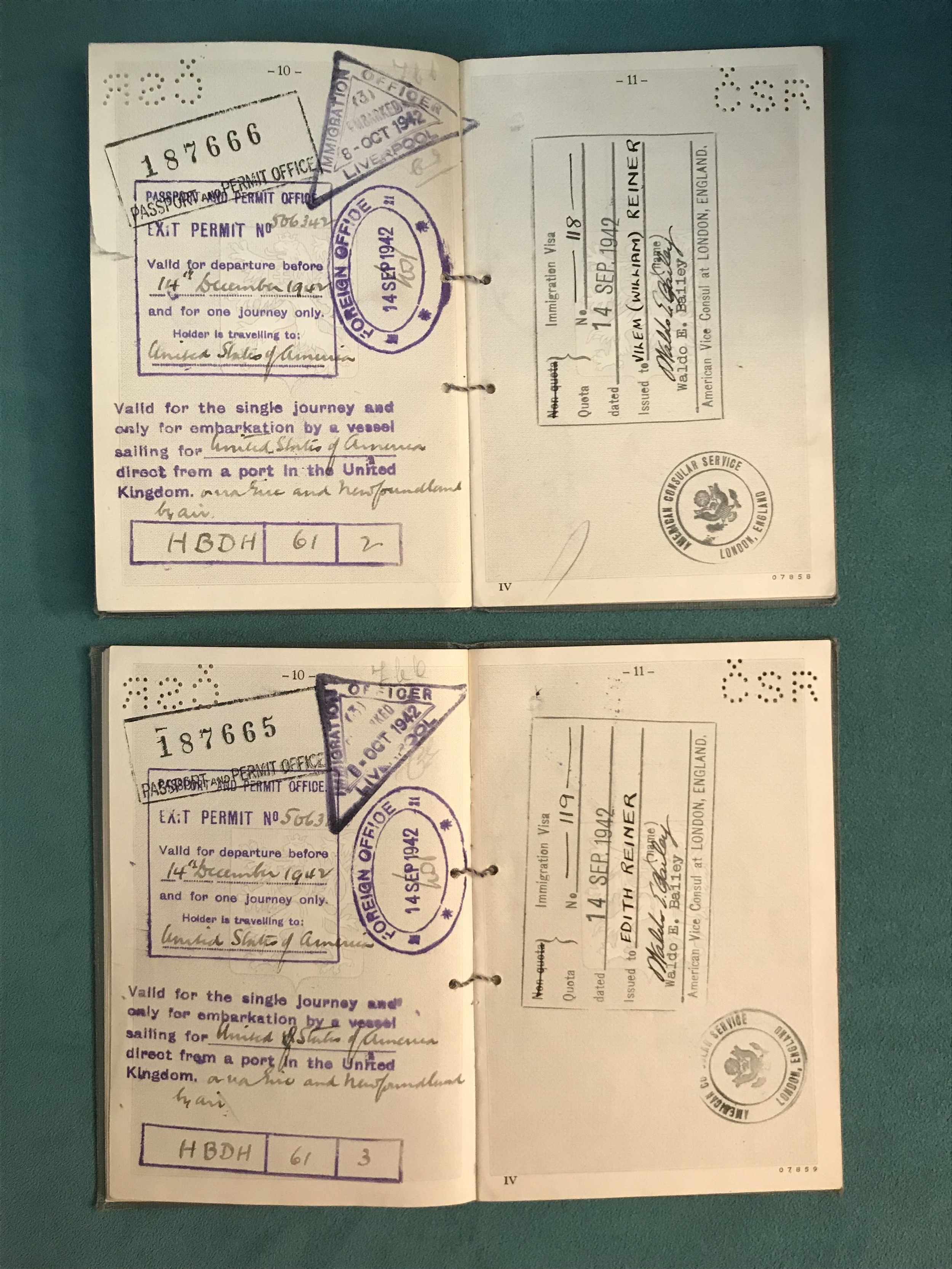

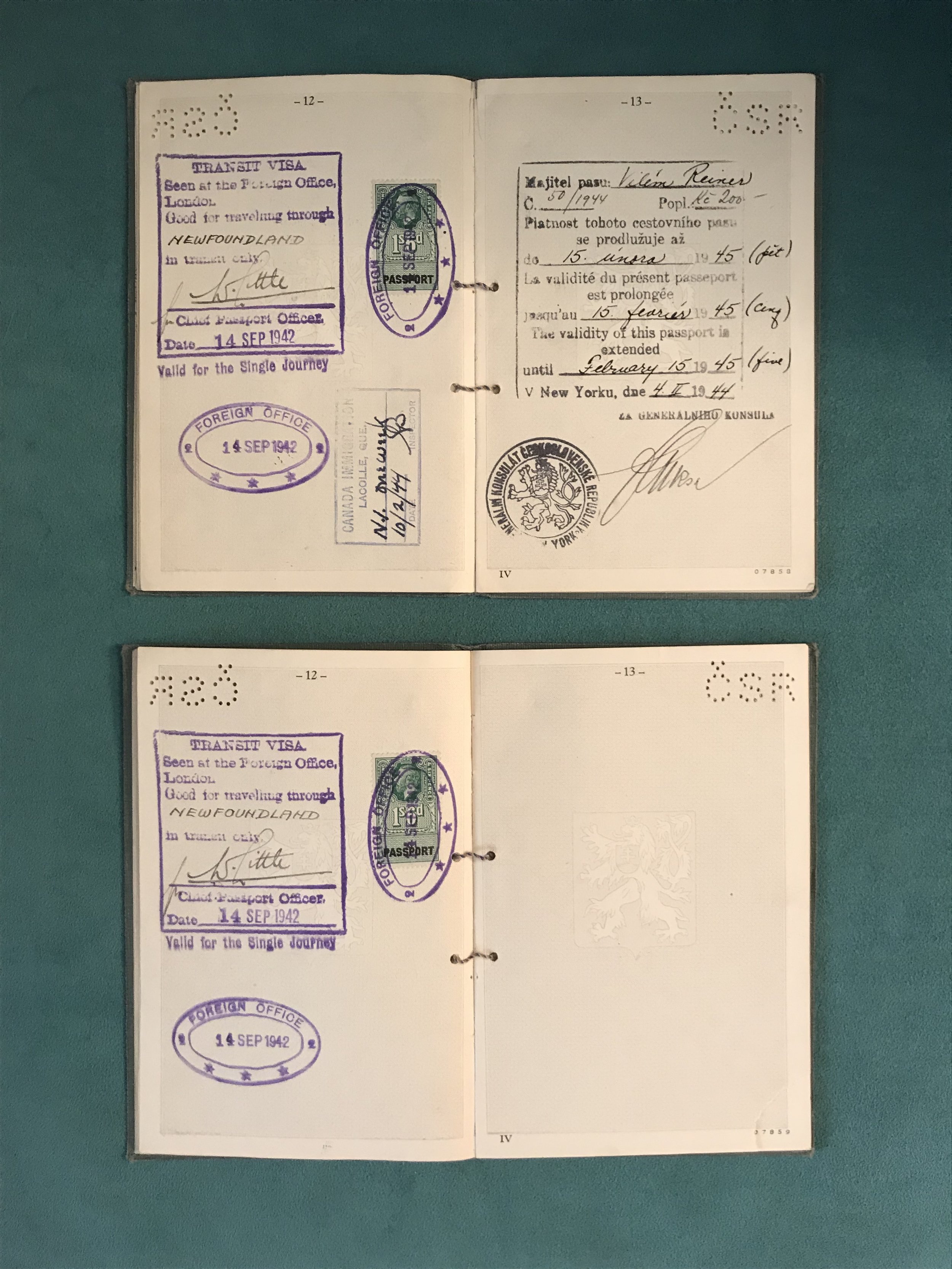

Late in 1942, U.S. visas were finally issued, and we set sail for America. The 28-day crossing was punctuated by the torpedoing of our boat as we sat on deck, life jackets at the ready. But not even the vaunted German armament technology was flawless as the missile turned out to be a dud. Just about a year after Pearl Harbor, we began our new life in New York. We survived. The years and decades which have followed were rich and rewarding.

How did this family manage to elude the real horrors of the century? That we were the recipients of letters from the cauldron of the Shoah rather than their writers. That we did not have to force out words such as those penned by my father’s twin sister from 1939 to 1941: And here I quote from my aunt Mitzi’s letters from occupied Czechoslovakia near Prague, telling of increasing woes and desperately begging for help from my recently arrived uncle safe in New York:

December 1939

“Meine Lieben, Hugo [my uncle] cannot expect to remain long at his job, and what will happen to people like that? Our plan relative to Bolivia has fallen into the water; San Domingo doesn’t look any more promising. The USA is our last resort. Papers report that visas, though with a long waiting period, are still available. Can we count on your help … the queue would have us waiting until 1944 or still longer.” March 1940 “Hugo has been let go … no work … possibilities for people like us? Hansi [my 7-year-old cousin] learns English.”

December 1940

“We are in dire economic straits... I make do as best as I can—floor installation, taking care of chickens, etc. The boy no longer in school is getting private lessons. We regret not having energetically sought ways to leave in the past; we are now trying to catch up. It looks as though there will be even more reason in the future to think of moving out.” 1941 A letter again requesting relatives in USA to facilitate documents to get admitted; also reporting that Mitzi and Hugo hear from many sources how enormously difficult it is to obtain U.S. visas. Maybe the relatives in the USA could contact a Senator.

1942

No more letters. It all ends with transports and then Auschwitz.

How come we, and a few others (my father’s brother, my aunt, his wife, my New York cousin among them) virtually glided by the catastrophe? My take on this is a blend of fortunate factors which characterized a portion—a small portion—of the vulnerable population. They had to be risk-takers—as they were in their earlier years when they broke with their roots to forge ahead in and with a new secular society. They had to have access to information which made them privy to the possibilities and the dangers—as my parents were on account of their occupations. They had to have a degree of pessimism or even cowardice—to acknowledge they might not be able to withstand, even with money, even with contacts, a tidal wave of catastrophe. They had to have the ability to reinvent themselves and be ready to do so—as they did first in their young adulthood, and then again in early middle age in alien settings. And there was the all-important element of simple dumb luck: the absent translator replaced by my mother, the bomb which destroyed our house but did not kill us, the torpedo which we saw coming at our boat, but failed to explode.

Jewishness. What part did this have to play in this story? My parents saw themselves as nonreligious Jews (no, not a paradox) whose lives ultimately were constrained and shaped by the undeniable fact that others saw them as Jews. They had an inner strength which amazes me (as had others whose trajectory paralleled theirs). Such strength comes to many out of spirituality based on their religion. For my parents, I have concluded, it grew out of a fierce commitment to family plus an unbreakable ethic which I now feel had its foundations in Torah.

And their commitment to learning, the life of intellect, was in their eyes congruent with their Jewish heritage. A footnote: I did not know that my secular father—with his proud command of six languages—also knew a seventh. Only when he was 80, reading Torah in Boston at his friend’s grandson’s Bar Mitzvah, did I become aware that he also knew Hebrew.

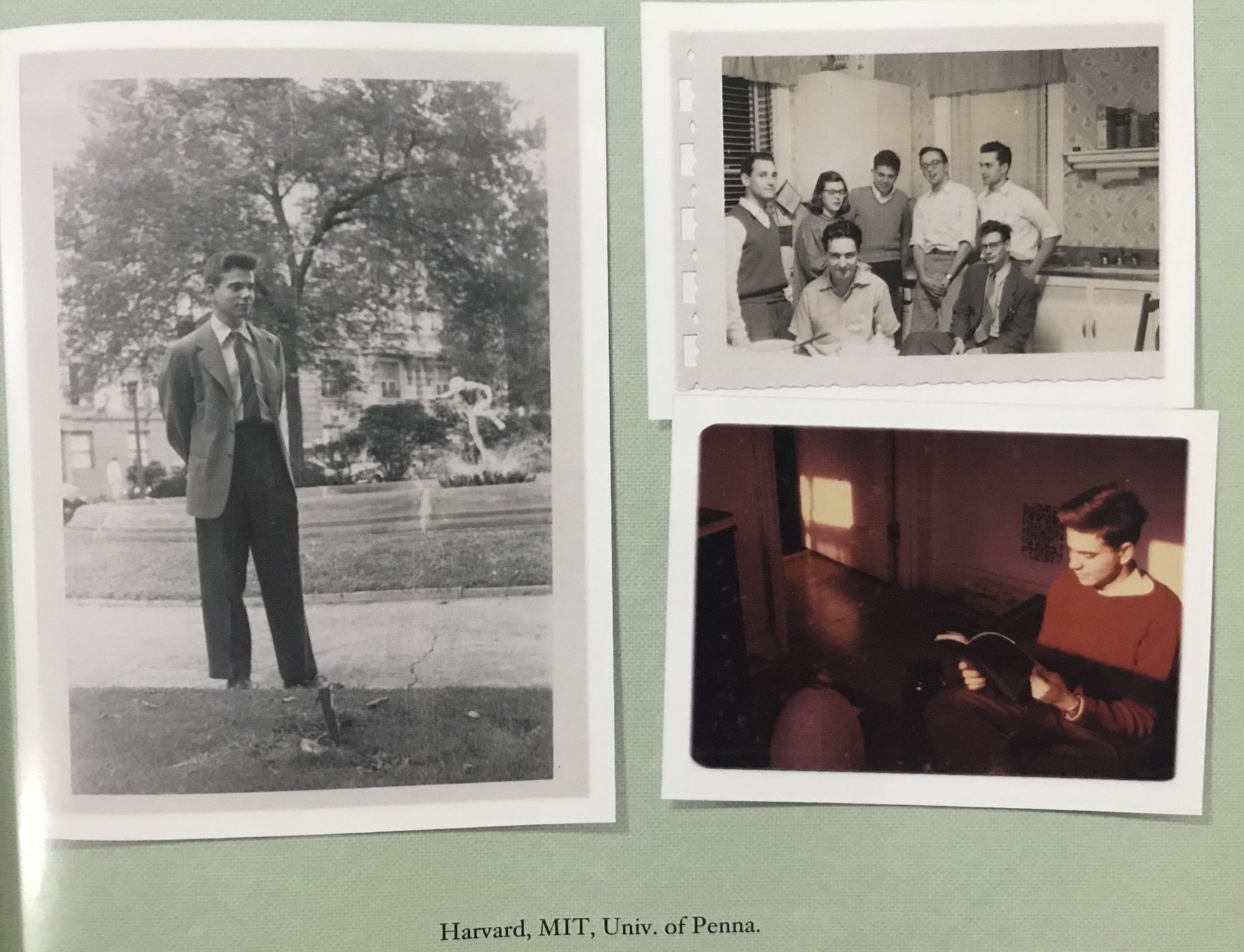

I have shared with you a story of passage which amazingly evaded personal horror. We lived through the war, avoiding the core of the Shoah. My family found the resources to rebuild our lives. More than that happened: It is hard to realize that out of all this, a wonderful life could ensue. In New York, my father again studied, worked, took exams to become once more an attorney specializing in retrieving assets and assuring restitution for Czech refugees.

What happened is all the more incredible as so many of my parents’ relatives and friends perished. The immediate postwar years were indeed burdened with this knowledge. I am sure my parents felt guilty on account of their escape and good fortune. I now realize that in fifty American years my father mentioned his twin sister and her family no more than five times. My mother surely struggled with the discovery that none of her six siblings nor their spouses lived through the Holocaust (but her 88-year-old mother walked out of Terezin and indeed came to spend some six turbulent years in New York).

“Survive:” to continue living, remain alive in spite of an ordeal; I parse the word “survive” and its etymology and choose to shift its meaning slightly. I take it to mean living above, beyond, to exceed the life that might have been. Indeed, I, my family, which now has blossomed with two more generations, and others like us, can only be said to have lived well. This is a “survive” which has its proactive components, as distinct from one this is passive, referring to a state of being.

No, we were not among the survivors who walked in and came out of Hell. Rather we skirted that world. I find myself thinking “there might I have gone.” That thought is part of me too. It speaks with love to my cousins, aunts, uncles, playmates whose life trajectory took that different path which might so easily have been my own. Otherwise, I know that the person I am was shaped by the passage to America. It strengthened my parents and probably me, even taught us how to look for doors to open. For those like ourselves, it seems to me that this relatively benign “survival” was if anything an opportunity. It also left us with an enormous sense of gratitude and thankfulness. It presented us with an incentive in some sense to repay. It also leaves me with appreciation and respect as well as sorrow for the many more whose survival path was more tragic and burdened.

“How the furniture, textiles, graphics resonate: straight from my parents’ Prague apartment.”

It is last year. I walk through the gallery. An exhibit of Friedl Dicker Brandeis’s work: the Bauhaus years through her last days in Terezin. How the furniture, textiles, graphics resonate: straight from my parents’ Prague apartment. It evokes the earliest memories I have of my surroundings. But it is the gallery’s last hall which holds me with the sharpest intensity. Taken to Terezin, Friedl took on herself the task of teaching art to the children trapped there. The exhibit bursts on me with a poignant item: The class list and grades for the girls and boys under her wings. Kitty Langendorf’s name leaps out at me. She was my first love, a laughing, tender, beautiful child at 7, my age. This hits more fiercely even than having earlier seen her name on the wall of the synagogue in Prague. And, oh yes, Friedl judged her painting that day as a good piece of work.

I close with fading decades-old memories and a dreadful love for Aunt Mitzi, Uncle Hugo, cousin Hansi, Teta Kamcha, Onkl Josef, just-married cousin Gretl, Kitty, and about 15 other close relatives who failed to live through events they did not anticipate until too late.

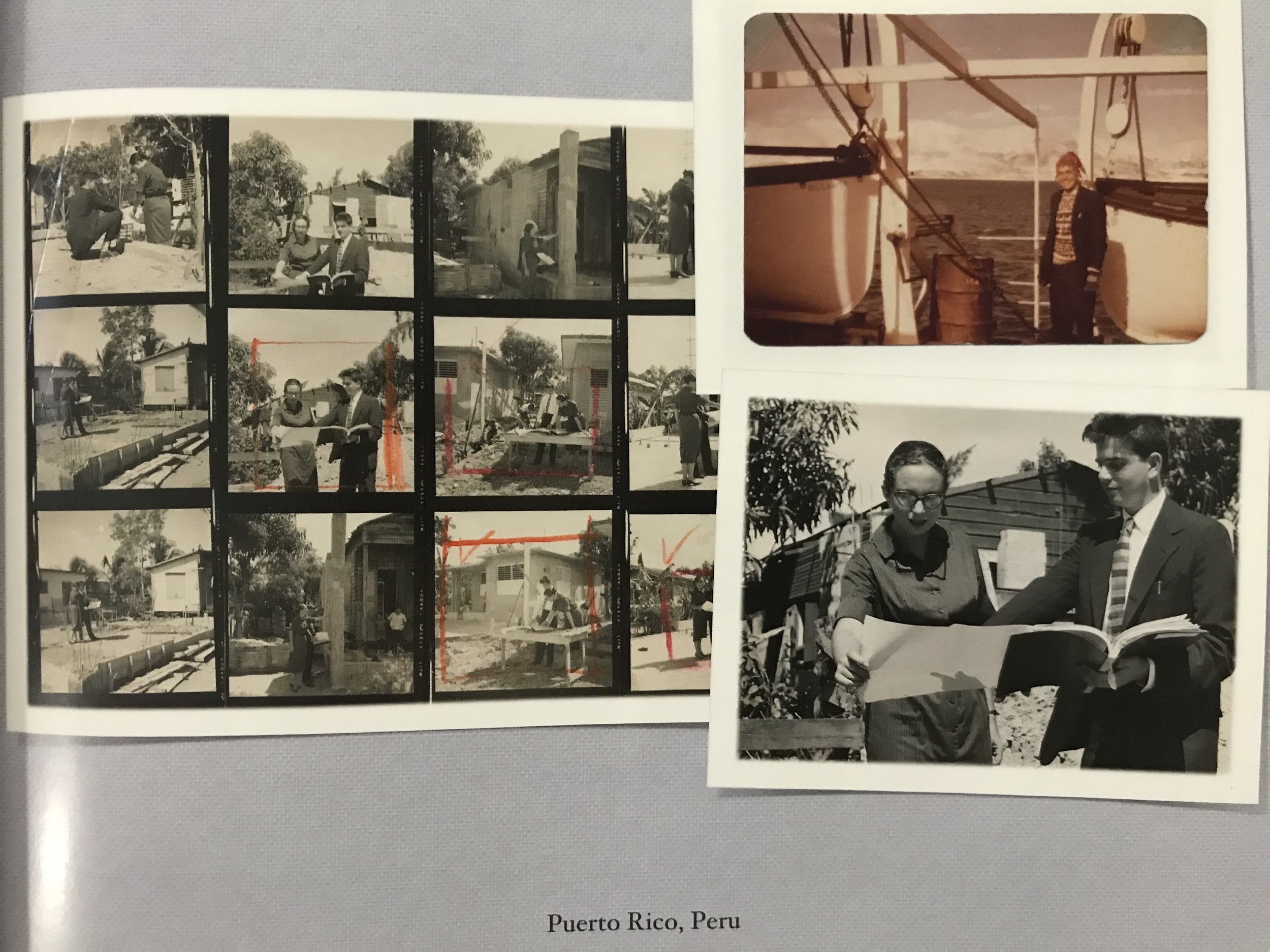

Tom Reiner went to Swarthmore, MIT and Penn, where he got his doctorate in urban planning. Tom taught at Penn and overseas through Fulbright and USAID assignments, but he always returned to teach at Penn, ending his career as Professor Emeritus. Because he taught for a year at the Technion, he learned to read Hebrew and became comfortable at BJ, which also suited his political outlook. He met his wife Susan Lieberman through a BJ connection, when his friends Esther Rivka and Julian Wolpert introduced them. They had an immediate connection when they discovered they were both involved with genealogy, had worked in Kiev, and had relatives who lived in Basabilbaso, Entre Rios, Argentina. Tom Reiner died in 2009.

Originally published at: https://www.bj.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Childhood-Memories-of-Survival-from-Prague-Tom-Reiner.pdf

For recordings of three interviews with Tom Reiner, please click to listen below: