Brief History of Czech and Slovak Jews

The country of Czechoslovakia was formed in October 1918, towards the end of the First World War and the collapse of Austria-Hungary. It comprised the regions of Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia, Slovakia and Subcarpathian Rus, with Czech, Slovak, Hungarian, German, Yiddish, Polish and Ukrainian spoken among the new population, though only the mutually intelligible Czech and Slovak –stylized as “Czechoslovak” - remained official languages. The newly formed state bordered Germany in the west and north, Austria and Hungary in the south, Poland in the north-east, and Romania in the south-east.

Although these borders remained in place only briefly – from 1918 until 1938 – they symbolize a period of relative prosperity and peace sometimes referred to as the “golden” era of the First Czechoslovak Republic. It was during this era that the first incarnation of the Society for the History of Czechoslovak Jews was established in 1928 by the Prague lodge of B’nai B’rith with the German name of Gesellschaft für Geschichte der Juden in der Čechoslovakischen Republik. It is therefore the territory within these borders that we look to when examining the history of Jewish life in Czechoslovakia, prior to, during, and after the existence of the First Czechoslovak Republic.

First Jewish settlements

While it is thought that Jewish traders have passed between Roman Legions and Germanic tribes at the time of the Roman Empire, we have no written record to confirm Jewish presence in what was to become Czechoslovakia until 965 CE, when Ibrahim Ibn Yaqub, a Jewish merchant sent to Bohemian lands by the Caliph of Cordoba (in present day Spain) reported that “Fraga [sic] is the largest city in terms of trade. Coming here…Slavs, Muslims and Jews.” We also know that Jews were granted permission to reside in Bohemia in 995 CE, after aiding the Byzantine Empire in fighting Bulgarian pagans in what is now Slovakia. The first records of Jewish settlements in Slovakia date back to the eleventh century, and the first record of a Jewish community in Bratislava (also known as Pressburg in German and Pozsony in Hungarian) dates back to 1251.

Middle ages and Hussite revolts

A number of medieval records attest to Jewish scholarship in the region. Rabbi Abraham ben Azriel of Bohemia, who lived in Prague during the twelfth century, published a book of liturgical poems called Bed of Spices (Arugat HaBosem), which contained forty Czech words. The book suggests that Jewish rabbis at the time wrote and spoke Czech as well as Hebrew, and remains a valuable source for studying medieval Czech.

Persecution and pogroms, partly influenced by the Crusades, persisted in the medieval period, and in 1254, Bohemian king Přemysl Ottokar II granted a number of protections to Jewish subjects. For the first time, Jews were eligible for positions in service to the crown and were deemed to be “king’s property”, a status that granted them protection by the king and his royal officers. Sixteen years later, Prague’s Jewish community built the New Synagogue. It is known today as the Old-New Synagogue, and remains the world’s oldest synagogue with a twin-nave design.

New Synagogue, built in Prague in 1270 (photo by Øyvind Holmstad)

Ottokar’s protective measures mirrored those of Andrew II, king of Hungary, which at the time included Slovakia. Andrew II regularly employed Jews and Muslims at court. He decreed in 1229 that the Jewish minority in Bratislava were to have equal rights to other citizens, and that they were to be represented by a Jewish mayor. The town’s Jewish community featured a wide range of occupations, from financiers to merchants, craftsmen, and even winemakers.

The fourteenth century saw a resurgence in anti-Semitism, culminating with the Easter Sunday pogrom in Prague’s Jewish Quarter in 1389, when an estimated 1,500 Jews were slaughtered. The King of Bohemia, Wenceslaus IV, offered some protections to Jews by enforcing their status as servants of the chamber, while simultaneously extracting large funds from the community by canceling debts owned to Jewish lenders by his princes.

During the fifteenth century, Bohemia, Moravia, and to a lesser extent Silesia and Slovakia became influenced by the Hussite movement, a pre-Protestant church reform effort led by priest Jan Hus. Some Jewish communities were sympathetic to the Hussites, whom they believed to be sent by God to repel Catholic oppression. The Church authorities in turn viewed the Hussites as a “Judaizing sect” because of their reverence for the Old Testament, their rejection of saints, and their criticism of Catholic leaders. Once the Catholic Church regained control in 1436, Jews were again subject to suspicion and discrimination, and were ordered to leave five crown cities in Moravia in 1454.

In Slovakia, the Bratislava City Council implemented a Papal decree that ordered all Jews to wear a red hooded cape in order to be visible from a distance, and in 1494, a blood libel resulted in the burning of several Jews in the town of Trnava. After the Battle of Mohacs in 1526, when the Kingdom of Hungary lost much of its southern land and moved the capital from Buda to Bratislava, Jews were expelled from most Slovak towns. In 1529, thirty Jews were burned at the stake in the village of Pezinok, and in 1572 all Jews were ordered to leave Bratislava, unless they converted.

Enlightenment and growing tolerance

In contrast to the Middle Ages, the sixteenth century saw relative tolerance of Jewish subjects in the Bohemian Kingdom, ruled over by Habsburg monarch Rudolf II (1576 – 1611). Jews were permitted to live outside the ghetto, to travel freely, to engage in trade, and to own land. They became doctors, astronomers, artists, farmers and bankers. Immigration from neighboring kingdoms increased, and the Jewish population in Prague almost doubled. It was during this time that the famed Rabbi “Maharal” Judah lived in Prague, later immortalized in nineteenth century tales of Golem. During the sixteenth century, the “Maharal” frequently presented his ideas to Rudolf II, and published an influential Torah commentary Gur Aryeh al HaTorah.

Podhradie- site of the Jewish quarter in Bratislava in the 17th century.

By the end of the seventeenth century, Jewish inhabitants of Prague are estimated to have numbered 11,000 – 13,000, an approximate 30% of the city’s population, and a reflection on immigration from Austria and Hungary in reaction to Turkish expansion as well as an edict expelling Jews from Vienna in 1670. A 1729 census of the Jewish population in Prague listed 330 dwelling houses inhabited by 2,335 families, 30 public buildings, and 2,300 artisans in professional guilds, including 158 tailors, 100 cobblers, 39 milliners, 20 goldsmiths, 37 butchers, 28 barbers and 15 musicians. In Bratislava, a Yeshiva was established in 1700, and the Jewish population grew from 189 in 1709 to 772 in 1736. By the eighteenth century, it had increased to 2,000.

In 1740 Maria Theresa ascended the Habsburg throne. Initially opposed to both Jews and Protestants, she ordered an expulsion (soon reversed) of all Jews in 1744, but later moderated her policies. In the 1760s, she granted state protections to Jewish subjects, forbade forced conversion of Jewish children to Christianity, and ordered the release of Jews who had been jailed on account of a blood libel in the Slovak village of Orkuta.

Maria Theresa’s eldest son and successor, Joseph II, pursued a policy of reform, with a number of “Tolerance Edicts” in 1781, which declared Jews to be “useful subjects of the Crown,” and enabled them to enter public life, take up any profession and study at non-Jewish institutions of higher education. Nevertheless, two restrictions continued to limit Jewish life. The Familiants Laws limited the Jews’ right to marry to the oldest son, and quotas continued to restrict the number of Jews able to reside in particular areas of the empire. Neither restriction was lifted until 1849, and a number of Bohemian and Moravian Jews emigrated to the United States in the meantime. One of them was Isaac Mayer Wise, a key figure in the development of Reform Judaism in the US.

In 1848, some 10,000 Jews lived in Prague and the Jewish Quarter was renamed Josefov (Josephstadt in German). However the so-called 1848 Spring of Nations revolutions against monarchical rule resulted in pogroms, and more Jews emigrated to the New World, including Adolph Brandeis – father of Louis Brandeis, the future US Supreme Court Justice.

Austria-Hungary and Emancipation

In 1867, the creation of Austria-Hungary led to the full emancipation of all Jews within the Empire, which included Bohemian, Moravian, Silesian, Slovak (known then as “Upper Hungarian”) and Subcarpathian territories. In 1895 the ‘Reception Law’ placed Judaism and Christianity on an equal footing, a measure that arguably increased Jewish influence while provoking further anti-Semitic sentiment. Anti-Jewish riots occurred in a number of towns in Upper Hungary (later Slovakia) in 1882 and 1883, and the Slovak Clerical People’s Party was formed in 1896, intent on limiting Jewish influence.

At the same time the Zionist movement grew, and the First Hungarian Zionist Convention was held in 1903 in Bratislava. The movement found advocates in Bohemian lands too, among them Max Brod, a prolific German-Jewish and later Israeli author, perhaps best known as Franz Kafka’s close friend and editor. A number of Austro-Hungarian Jews who later rose to global prominence began their lives in what would later become Czechoslovakia. Sigmund Freud was born in the Moravian town of Příbor. Architect Emery Roth was born in Sečovce, in Slovakia, composer Gustav Mahler was born in eastern Bohemia, and artist Anna Ticho was born in Brno, in Moravia.

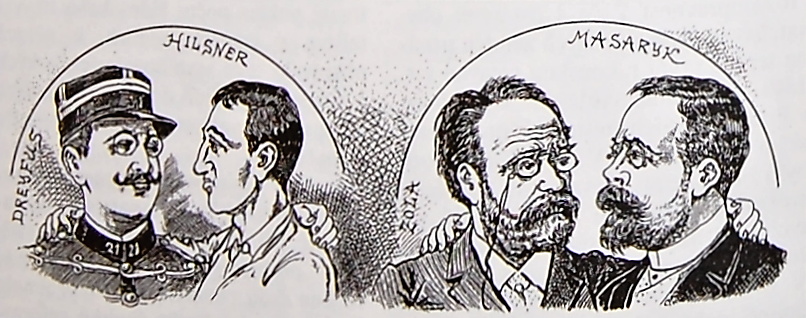

Contemporary caricature comparing the Hilsner affair to the Dreyfus affair, 1900.

The precarious balance between successful Jewish assimilation, particularly in urban centers, and persistent anti-Semitism, more common in rural areas, came to a head in 1899, when a Jewish man called Leopold Hilsner was accused and later convicted of ritual murder of a Czech woman near the town of Polná. The Hilsner Affair proved polarizing, but Hilsner found the future Czechoslovak President Thomas Garrigue Masaryk among his staunchest defendants. Masaryk argued strongly against anti-Semitic blood libels, and although Hilsner was still sent to prison, emperor Franz Josef I himself commuted his sentence, and Austria-Hungary’s last Emperor Charles I eventually pardoned him just before the end of the First World War in 1917.

Of Austria-Hungary’s 2,250,000 Jews, 320,000 joined the army during the First World War, including 76 rabbis, who were all given officer rank. And while Jews made up about 5% of the total population, they made up 18% of reserve officer corps. All Jewish soldiers were provided with religious services and an opportunity to mark High Holidays during the war. Some 40,000 Austro-Hungarian Jews were killed in action.

The First Czechoslovak Republic

When Austria-Hungary collapsed at the end of First World War, it was broken up into smaller states structured along ethno-geographical boundaries. The new democratic republic of Czechoslovakia, established in 1918 and headed by President Thomas Garrigue Masaryk, brought together Bohemian, Moravian and Slovak territories, encompassing Czech, German, Silesian, Moravian, Jewish, Slovak, Polish, Ukrainian and Hungarian populations. The 1921 census showed that 180,534 people identified as Jews by religion (1.33% of the population), which rose to 354,000 (2.4%) by the time of the 1930 census.

A number of Jewish individuals gained prominent positions within the newly established Czechoslovak society. In spite of making up less than 3% of the total population, 18% of all Czechoslovak university students were Jewish, and the newly formed Jewish Party (Židovská strana) won two seats in Parliament by 1929. A number of prominent politicians in the new republic came from Jewish families, most notably Ludwig Czech (Minister of Social Care and later of Public Affairs) and Bruno Kafka (Franz’s second cousin and member of the National Assembly in 1921 and 1922). By 1930, 12% of the population in Bratislava was Jewish, and by 1938, the city had a Jewish deputy mayor and three elected Jewish city council representatives.

Karel Poláček, noted Czechoslovak author of Jewish descent.

Czech-Jewish literature flourished. Jiří Langer – a friend and a contemporary of Franz Kafka, published a collection of Hasidic legends called Nine Gates in 1937. Karel Poláček became a popular satirist, while Viktor Fischl, Hanuš Bonn and Jiří Orten were part of an emerging wave of Czech language poets.

The inter-war Jewish population became increasingly urban and secular – while the 1921 census recorded 205 Jewish communities in the Czech lands, this number decreased to 170 in 1931. This was particularly true in Bohemia, where 69% of Jews lived in cities - 40% of them in Prague - and where 43.8% of Jewish individuals intermarried between 1928 and 1933.

Moravian and Silesian Jews tended to live in smaller cities, most notably Brno and Ostrava. 30% of marriages with a Jewish Moravian partner were intermarriages. In Slovakia, the population spread was even more balanced between urban centers and rural settings, and only 9% of Jews intermarried. In Subcarpathian Rus, in the most eastern part of the country, only 1.3% of Jews intermarried. It was also in Subcarpathian Rus that Yiddish was most widely spoken, and where Hasidism was most widespread in the country.

Anti-Semitic activities continued in the new republic, and by the 1930s, the increasingly populist Slovak People’s Party encouraged anti-Semitic rioting, and Jewish boxers and wrestlers took to the streets to defend their communities. One of them was Imi Lichtenfeld, who later emigrated to Israel, where he developed the Israeli martial art of Krav Maga.

Nazism and the Second World War

The period of democracy and prosperity that marked the first Czechoslovak Republic, came to an abrupt end with the Munich agreement in September 1938. Guided by the policy of appeasement, the United Kingdom, France and Italy agreed to let Hitler take over the Czechoslovak border region called Sudetenland, with the hope that appeasement would pacify the German leader’s expansionism and prevent war in Europe. Most of the 27,073 Jews who had lived in Sudetenland attempted to escape into the Bohemian and Moravian interior, which became a Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia after the Nazi occupation on 15 March 1939.

Slovakia became a client state of Nazi Germany governed by the predominantly Catholic and anti-Semitic Slovenská Ľudová Strana, led by priest Jozef Tiso. Southern parts of Slovakia as well as Subcarpathian Rus were annexed by Hungary, as part of the First Vienna Award from November 1938.

The Central Office for Jewish Emigration was set up under the leadership of Adolf Eichmann for the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, with the aim to expel all Jews and to confiscate their property. Only 26,000 Jews of an estimated Jewish population of 118,310 were able to emigrate legally through the office. Several thousand more – mostly young - Jews escaped illegally through Poland and Slovakia. Many of them joined the Czechoslovak Army in exile.

Between March and September 1939, over a thousand children were hastily put on trains to the United Kingdom as part of the Kindertransport rescue efforts. Among the passengers were Benjamin Abeles, later a US physicist whose research led to technology that powered the Voyager spacecraft, and Karel Reisz, British filmmaker best known for the pioneering realist drama Saturday Night, Sunday Morning.

By September 1941 all Jews in the Protectorate were ordered to wear a yellow badge, and Jewish children were no longer permitted to attend non-Jewish schools. The Prague Jewish Community was ordered to register all Jews, confessional or not. The first transports of Jews to concentration camps began in 1939 to Nisko in Poland, and continued to Lodz in Poland and Minsk in Belarus in 1941.

Theresienstadt, the “model” ghetto

Leaders of the Prague Jewish Community were compelled to work with the Nazi regime in establishing the ghetto of Theresienstadt (Terezín in Czech), 60km north of Prague. The so called “model” ghetto was unique in that it was not administered by the SS Main Economic and Administrative Office, but by the Central Office for Jewish Emigration in Prague and a Jewish self-government of the Council of Elders.

Professional musicians who were interned at the camp performed classical and jazz concerts for small, select groups of inmates. Academics delivered lectures, and artist inmates secretly depicted life at the camp. Pianist Viktor Ullman composed over twenty works at Theresienstadt. A library was organized that grew to hold 100,000 volumes and employ 15 librarians, and some of the estimated 15,000 children who passed through the camp received clandestine school lessons, and were able to compose poetry and prose, immortalized in magazines like Vedem (We lead).

Vedem, a literary magazine published by schoolboys in Teresienstadt.

The camp’s cultural life made it an ideal candidate for a visit from the International Red Cross in 1944, for which the Nazis staged the concentration camp as a peaceful “Jewish settlement,” deporting thousands of inmates to Auschwitz to make the camp appear less crowded, and creating false shops, cafes and a school, as well as a 90 minute propaganda film showing yellow-star-wearing men, women and children at the camp working, reading, playing sports and tending to their gardens. The reality, of course, was drastically different. In spite of the rich cultural heritage that detainees at Theresienstadt left behind, living conditions were cramped, and malnutrition, infectious illnesses and exhaustion were rampant, preventing most inmates from accessing the activities the camp is known for. Of the approximately 155,000 people sent to Theresienstadt, 35,000 died there from hunger and disease, while 83,000 were deported. Most of the deportees were murdered at extermination camps across German occupied territories.

The Bratislava Working Group and the Slovak Resistance

Slovak Jews had been stripped of civil rights by 1941 through legislation called the Jewish Code, which forced them to wear a yellow badge and forbade them to intermarry. 12,300 Jewish-owned businesses were confiscated or liquidated. All Jewish organizations were forced to disband, and combine into one Jewish Center (Ústredňa Židov), which was to assist with deportations, provide welfare and housing for those Jews that was were stripped of their jobs and homes, and to help implement Nazi decrees among Jewish communities.

Gisi Fleischmann, leading member of the Bratislava Working Group

The Jewish Center proved instrumental in moderating the ill-effects of the Nazi-sympathetic Slovak regime during the war. The Emigration Department, headed by Gisi Fleischmann, helped secure emigration papers, and the Education and Culture Department succeeded in setting up 61 schools for Jewish children that were excluded from public education. By 1941, some members of the Center - including Andrew Steiner, who later became a respected US architect - began to rally around Gisi Fleischmann to establish an underground resistance effort called the Bratislava Working Group (Pracovná Skupina in Slovak) , intent on subverting planned deportations of Slovak Jews.

At the start of the war, the Slovak government reached an agreement with Germany to pay 500 Reichsmarks for each family that Germans would deport from the country. In return, the Slovak government would be able to confiscate the property left behind. Deportations began in March 1942, and 58,000 Jews out of a population of 89,900 recorded in the 1940 census were transported. Those who remained were either exempt because they converted to Catholicism before 1939, or because they were working at one of the three Slovak forced labor camps – Sereď, Vyhnie, and Nováky.

In October 1942, the transports stopped for two years, in large part thanks to the Bratislava Working Group. A leading member of the group and relative of Fleischman called Rabbi Michael Dov Weissmandel led an effort to secure funds to bribe Nazi officials to delay individual transports, and worked hard to lobby both Slovak and international Catholic leaders to protest the deportations on moral grounds. In 1943, the Vatican condemned the renewal of deportations and the Slovak episcopate issued a letter condemning anti-Semitism. The group also worked to collect coded accounts from escapees in Poland describing exterminations, and helped smuggle escaped deportees in Poland back to Slovakia over the mountainous border.

In August 1944, the Bratislava Working Group supported the Slovak resistance in launching an attack on Tiso’s government. The resistance numbered 60,000 troops and initially took over large parts of eastern and central Slovakia, liberating a number of concentration camps and gaining more troops from the liberated – primarily Jewish and Roma – inmates.

Nevertheless, the German counter-offensive proved too strong. By October 1944, Nazi troops regained Slovak territory, and murdered most of the Jewish, Roma and Slovak partisan fighters. Few - including Andrew Steiner - managed to escape into the mountains and survive the war, but Gisi Fleischmann herself was deported to Auschwitz and later killed, as deportations resumed. Rabbi Michael Dov Weissmandel managed to jump off his deportation train to Auschwitz, and in spite of a broken leg reached a hideout in Bratislava, before escaping to Switzerland and eventually the United States. By 1944, deportations also reached Hungary-occupied Slovakia and Subcarpathian Rus. An estimated 130,000 Jews from these regions were transported to Auschwitz, out of an approximate population of 145,000.

The Holocaust represents the biggest decimation of Czechoslovak Jews in history. It has been estimated that out of a total pre-war population of 354,000, the Nazi regime killed 80,000 Jewish people from the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, 71,000 from the Slovak State, and 130,000 from Hungary-occupied Slovakia and Subcarpathian Rus.

Post-war Czechoslovakia and communism

A small number of Czechoslovak Jews survived the war in concentration camps, through hiding, and most often in exile. In the east, 15,000 Subcarpathian Rusyn Jews survived, of whom at least 8,000 migrated west into Czechoslovakia once Subcarpathian Rus was annexed by the Soviet Union in 1945. Most of the Jews that remained in Subcarpathian Rus left in the 1970s following the Jackson-Vanik amendment, which enabled Soviet emigration as part of a trade agreement. The last Soviet census of 1989 registered only 2,700 Jews in the region.

An estimated 30,000 Jews lived in Slovakia in 1946, and 24,395 people were registered as residing in Jewish communities in the Czech lands in 1948. Jewish survivors within Czechoslovakia mostly lost their family connections and livelihoods. Some were viewed with suspicion because they registered German or Hungarian nationality before the war.

Disputes over property ensued, and restitution tended to be slow or not forthcoming. Property disputes resulted in pogroms in Slovakia, most notoriously in Topoľčany in 1945, where 48 people were seriously injured. Similar riots followed in 1946 in Bratislava and Žilina in northern Slovakia. Large numbers of Jewish survivors in Slovakia emigrated, primarily to what was to become Israel, where statistics show that 18,247 immigrants born in Czechoslovakia arrived by 1949. The post-war Czechoslovak government supported the establishment of a Jewish state, and helped train Israeli soldiers as well as transferring arms and ammunition to the Israeli army.

The postwar government recognized 51 Jewish religious communities in the Czech lands, and 79 in Slovakia. The Council of Jewish Religious Communities in Bohemia and Moravia and the Slovak Central Association of Jewish Religious Communities were established after the war, eager to renew religious life, as well as to address social welfare and restitution. And while a number of pre-war Jewish organizations registered with the Ministry of the Interior to continue their pre-war activities, they struggled with lack of membership.

In 1948, the Communist party, heavily backed by the Soviets, staged a coup, and the democratic Czechoslovakia became an authoritarian Soviet satellite state, forcing thousands of Jewish and non-Jewish citizens to emigrate. The 1950 census shows that an estimated 14,000 – 18,000 Jews remained, although these numbers need to be treated with caution, as many citizens may not have voluntarily divulged their Jewish ethnicity or religion. A purge in 1952, centered around the Slánský show-trials, led to further infringements on liberties. 11 leading Communists, eight of them Jews, were charged with Zionism among other “crimes,” and sentenced to death. Religious activities - of Jews as well as Christians - were suppressed and closely monitored. Foreign Jewish organizations like the JDC (Jewish Joint Distribution Committee) were expelled, and emigration became restricted.

Historical accounts of Jewish life under communism in Czechoslovakia are scarce. Yet even as religious Jewish identity was diminished and most Jews willingly or fearfully concealed their “Jewishness”, secular Jews continued to live within the country and take up a wide range of professions. A number of Jewish authors continued to publish in spite of tight censorship. Ludvík Aškenazy published Dětské etudy (Children’s Etudes; 1955) - short sketches about everyday experiences with his young son. Norbert Frýd’s Krabice živých (A Box of Lives; 1956) told a story from a Nazi prison camp in the last year of the war, and Arnošt Lustig’s Noc a naděje (Night and Hope; 1957) tackled the theme of Nazi camps.

By the mid-1960s, Jewish themes once again featured prominently in Czechoslovak literature, both in non-Jewish works like Josef Škvorecký’s Sedmiramenný svícen (The Menorah; 1964), and Jewish ones, including Ladislav Grosman’s Obchod na korze (The Shop on Main Street; 1965), and J. R. Pick’s Spolek pro ochranu zvířat (Society for the Protection of Animals; 1969). These more daring literary works are emblematic of a period of liberalization in Czechoslovakia that culminated in protests during the Prague Spring of 1968, when Czechoslovak Jews reconnected with the international Jewish community. The Soviets invaded to crush the protests, and a period of repression followed, during which roughly one-third of Czechoslovak Jewry emigrated to Israel, the US, Canada, Australia and western Europe.

Those who remained continued to exist and even thrive in communist Czechoslovakia during the post-Prague Spring period of “normalization”. Jewish actor Miloš Kopecký, whose mother perished in the Holocaust, became one of the most popular TV stars of the communist regime. Dušan Klein, who - together with his mother and brothers - survived Theresienstadt, directed some of the most beloved films and television programmes of the 1970s and 1980s. Many Jews joined the dissident movement, like Karol Sidon, an author and playwright, who together with future Czechoslovak president Václav Havel, signed the anti-communist Charter 77. Nevertheless, visibility of Jewish life in late-era communist Czechoslovakia was limited, and Sidon emigrated to West Germany in 1983 in order to pursue Jewish studies at Heidelberg University.

The Velvet Revolution and the dissolution of Czechoslovakia

Chief Rabbi of Prague, Karol Sidon, in conversation with Václav Havel

The communist regime collapsed with the Velvet Revolution in 1989, when Czechoslovakia once again became an independent democracy, led by president Václav Havel. Havel was the first leader of a post-communist country to visit Israel, and headed a government that returned most property owned by Jews before 1938 to their families. The Jewish Museum in Prague, which was seized by the state in 1950, was returned to the Jewish community under the jurisdiction of the Federation of Jewish Communities. Karol Sidon returned to Czechoslovakia, and became the chief rabbi of Prague.

Interest in Jewish literature surged, with publication of collected works by Orten, Poláček and František Langer, while Jiří Kovtun’s Tajuplná vražda (The Mysterious Murder, 1994) - a powerful account of the Hilsner trial - became a bestseller. Czech Jews continued to feature prominently in public life. Michael Žantovský served as Ambassador to the United States, Israel and the United Kingdom. Jan Fischer, whose father was a Holocaust survivor, became Prime Minister from 2009 to 2010. Fedor Gál, a sociologist who was born to Slovak parents in Theresienstadt (Terezín) in 1945 and who supported the dissident movement in the 1970s and 1980s, co-founded the first nationwide, privately owned television station Nova in 1994, and became a prolific commentator on Czechoslovak politics and society. Many Jewish individuals whose heritage was kept secret under communism, began to discover and rediscover their ethnic, cultural, and religious roots.

In 1993, Czechoslovak leaders amicably agreed to split the country into Czech Republic and Slovakia. Both new countries saw a resurgence of Jewish life, even as the population of self-identifying Jews remained a fraction of its pre-war size. Today, Czech Republic is said to be the least religious country in the world, with 72% of the population declaring itself irreligious, according to a 2015 Pew Research Center study. Although the last census from 2011 found only 1,474 people who practiced Judaism, it is harder to estimate how many more secular Jews live in the country.

Most recent estimates approximate the Jewish population of Prague between 7,000 and 15,000 people, with much smaller Jewish communities in Brno, Olomouc, Karlovy Vary, Ostrava and Teplice. The Federation of Jewish Communities provides updates on Jewish developments, and the Lauder School in Prague provides full-time Jewish education from kindergarten through high school, while Charles University in Prague, and Palacky University in Olomouc house a center for Jewish studies. The Jewish quarter of Prague is well preserved and six synagogues are open across the capital. The site of Theresienstadt is now a museum and research center funded by the Czech Ministry of Culture with 250,000 visitors a year.

The Slovak Jewish community is estimated to be 2,600 people, mostly residing in Bratislava, with smaller numbers in Prešov, Nové Známky, Nitra and Trnava, which makes it the smallest Holocaust-surviving Jewish community in Europe. While the Jewish quarter in Bratislava was demolished in the 1960s to make way for a new social housing development, there are over a 100 synagogues across Slovakia, including the large Heydukova Street Synagogue in Bratislava and the Pushkinova Street Synagogue in Košice.

Accounts of anti-Semitism persist in Slovakia. Three Jewish cemeteries in Levice, Zvolen and Košice were vandalized in 2002 and 2003. In 2016, the neo-Nazi “People’s Party” – which models itself on Josef Tiso’s war-time government, won 14 seats in the Slovak National Council. Nevertheless, efforts remain to encourage the preservation and growth of Jewish life. The Museum of Jewish Culture opened in Bratislava in 1993 and is operated by the Ministry of Culture. The Slovak Jewish Heritage Center was established in 2006, in order to research, document and promote Jewish heritage in Slovakia, and has recently launched the Slovak Jewish Heritage route – a tourist and educational trail through key Jewish sites across the country.

Compiled by Pavla Rosenstein

Sources:

http://www.yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Czechoslovakia, http://www.yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Bohemia_and_Moravia, http://www.yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Slovakia, http://www.yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Reception_Law_of, http://www.yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Familiants_Laws, http://yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Weissmandel_Mikhael_Dov_Ber, https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/czech-republic-virtual-jewish-history-tour, http://www.yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Hilsner_Affair, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/czechoslovakia, https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn1000172, https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/pa1163181, https://www.jewishmuseum.cz/program- a-vzdelavani/vzdelavani/cyklus-nase-20-stoleti, http://www.vedem-terezin.cz/vedem-1rocnik-1943.html, https://digitalcommons.northgeorgia.edu/papersandpubs/vol1/iss1/5/, https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/hussites, https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/fedor-gl, http://www.academia.edu/8401316/What_did_it_mean_to_be_Loyal_Jewish_Survivors_in_Post-War_Czechoslovakia_in_a_Comparative_Perspective, https://archive.jpr.org.uk/download?id=2796, https://www.jta.org/2011/08/29/global/in-slovakia-being-strategic-about-preserving-jewish-heritage,

Further reading:

Kateřina Čapková, Češi, Němci, Židé? Národní identita Židů v Čechách, 1918–1938 (Prague, 2005); The Jews of Czechoslovakia: Historical Studies and Surveys, vols. 1–3 (Philadelphia, 1968–1984);

Dušan Čaplovič et al., Racial Violence Past and Present, trans. Martin R. Ward (Bratislava, 2003); Cohen, Gary: The Politics of Ethnic Survival: Germans in Prague, 1861–1914. (West Lafayette, Indiana 1981, 2nd edn 2006);

Michal Frankl and Jindřich Toman (eds.): Jan Neruda a Židé. Texty a kontexty. (Prague 2013); Frommer, Benjamin: National Cleansing. Retribution against Nazi Collaborators in Postwar Czechoslovakia. Cambridge, and New York. (2005, Czech version in 2010);

Alena Heitlinger: In the Shadows of the Holocaust and Communism: Czech and Slovak Jews Since 1945 (London and New York, 2017); Frankl, Michal, and Miloslav Szabó: Budování státu bez antisemitismu? Násilí, diskurz loajality a vznik Československa (Prague 2015);

Hillel J. Kieval, Languages of Community: The Jewish Experience in the Czech Lands (Berkeley, 2000); Hillel J. Kieval, The Making of Czech Jewry: National Conflict and Jewish Society in Bohemia, 1870–1918. New York and Oxford (1988, Czech version in 2011);

Otto Dov Kulka: ‘History and Historical Consciousness. Similarities and Dissimilarities in the History of the Jews in Germany and the Czech Lands 1918–1945’, Bohemia 46, no. 1: 68–86 (2005);

Jan Láníček: Czechs, Slovaks and the Jews, 1938-48: Beyond Idealizaiton and Condemnation. (Palgrave Macmillian 2013);

Zdeněk Lederer: Ghetto Theresienstadt. (London1953); Ezra Mendelsohn, The Jews of East Central Europe between the World Wars (Bloomington, Ind., 1983);

Kevin McDermott: ‘A ‘Polyphony of Voices’? Czech Popular Opinion and the Slánský Affair.’ Slavic Review, vol. 67, no. 4: 840-65 (2008);

Pavol Mešt’an, Anti-Semitism in Slovak Politics, 1989–1999, trans. Martin R. Ward (Bratislava, 2000); Peter Meyer, “Czechoslovakia,” in The Jews in the Soviet Satellites, ed. Peter Meyer, Bernard D. Weinryb, Eugene Duschinsky, and Nicolas Sylvain (Syracuse, N.Y., 1953).

Peter Meyer: ‘Czechoslovakia’, in Peter Meyer, Bernard D. Weinryb, Eugene Duschinsky, and Nicolas Sylvain, eds. The Jews in the Soviet Satellites (1971 Westport, Conn.: 49–206);

Tomáš Pěkný: Historie Židů v Čechách a na Moravě. (Prague 1993, 2nd ed. 2001);

Aviel Roshwald: ‘Jewish Identity and the Paradox of Nationalism’, in Michael Berkowitz, ed. Nationalism, Zionism and Ethnic Mobilization of the Jews in 1900 and Beyond. (Leiden: 11–24, 2004);